What I Look for When Evaluating a Data Stack

Image created by the author

How We Got Here

Before evaluating a data stack, it helps to understand how we got here.

What people call the “modern data stack” evolved over time as teams moved from on-prem systems to cloud warehouses, adopted ELT patterns, and added specialized tools to solve specific problems.

Each step made sense in isolation: cloud storage lowered costs, modular tools increased flexibility, and self-service analytics increased the speed of decision-making. Over time, these choices layered on top of one another.

The result is a powerful stack spread across many tools, teams, and abstractions.

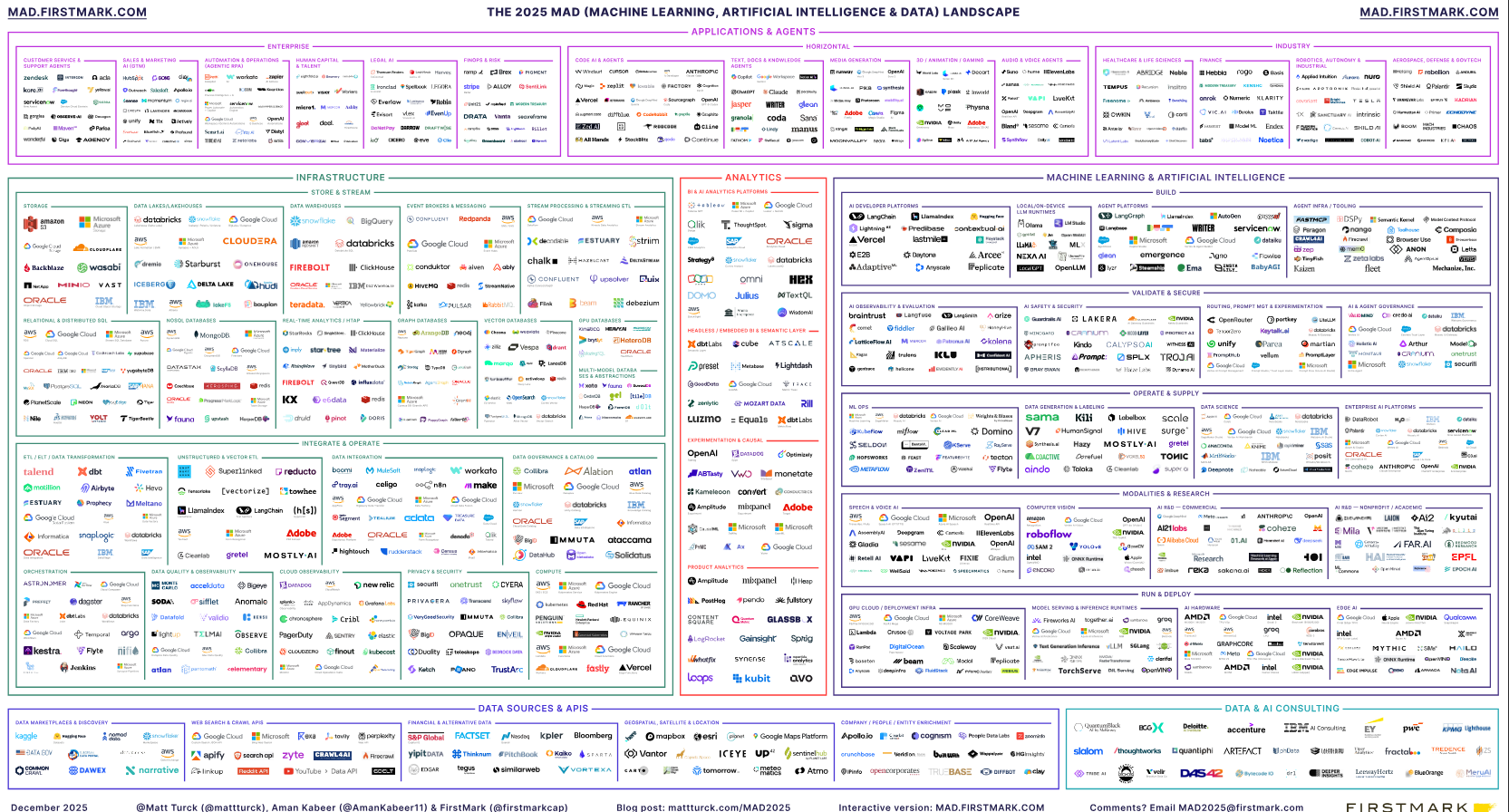

The MAD Ecosystem | Source: mattturck.com

Frameworks like the Modern Analytics Data (MAD) Landscape are useful for understanding the breadth of the ecosystem. They show just how many categories and tools now exist around ingestion, transformation, orchestration, governance, and consumption.

After working across different data systems, I’ve found that the long-term success of a data stack has less to do with individual tools and more to do with how the system behaves over time, especially as teams grow, requirements change, and complexity accumulates.

The following principles reflect how I evaluate data stacks.

Design for Understanding

A powerful system that only its original authors understand is a liability.

For example:

- A transformation layer with deeply nested abstractions might reduce duplication, but if debugging requires tracing logic across multiple files and conventions, engineers spend more time understanding the system than improving it.

- In contrast, a stack with consistent naming, predictable folder structure, and clear patterns makes it easy for a new engineer to follow the flow end to end, even if it’s slightly more verbose.

Sophisticated abstractions can be useful, but clarity is what keeps systems usable six months later, after the original context is lost.

Clear Ownership and Boundaries

Unclear responsibility across the pipeline often leads to data problems.

Common signs include:

- Ingestion jobs fail and it’s not clear who owns the fix

- Transformation logic is spread across teams without a defined boundary

- Downstream consumers don’t know who to contact when data looks wrong

A more stable setup assigns responsibility by layer and makes the handoffs explicit:

- One team owns ingestion, raw datasets, and upstream data contracts

- Another team owns transformations and modeled datasets used downstream

- Expectations at each handoff are defined so teams know where their responsibility begins and ends

When responsibilities are aligned to pipeline layers, issues are easier to diagnose and resolve.

Observability and Trust

If something goes wrong, how quickly can the team understand what happened and why?

Consider two scenarios:

- A pipeline silently produces stale data because an upstream source changed schema, but nothing alerts the team. The issue is only discovered weeks later through a business discrepancy.

- A pipeline surfaces freshness checks, row-count anomalies, or schema mismatches immediately, allowing the team to respond before incorrect data propagates.

Silent failures are the hardest to recover from. Systems that surface issues early reduce downstream impact.

Designed for Change, Not Perfection

Data needs evolve over time.

This becomes apparent when:

- A new data source is added with different assumptions

- A column that was once optional becomes required

- Reporting needs shift in ways the original design didn’t anticipate

Stacks designed for change tend to:

- Isolate raw data from business logic

- Minimize tight coupling between layers

- Make migrations incremental rather than large rewrites

Requirements change faster than designs, so systems that anticipate evolution are more resilient.

Human Cost and Cognitive Load

Design choices shape how people work with a system.

Cognitive load shows up when:

- A pipeline depends on a specific run order that isn’t documented

- A dashboard only makes sense if you know its history

- A process relies on people already knowing how it works

More sustainable stacks reduce this burden:

- Assumptions are documented

- Defaults are safe

- Engineers don’t need to keep large amounts of context in their heads during incidents

The most reliable systems are the ones people can reason about when they’re tired, under pressure, or new to the codebase.

A Practical Checklist for Evaluating a Data Stack

This checklist isn’t meant to dictate tooling decisions.

It’s designed to help teams ask better questions before committing to a stack.

Clarity & Usability

- Can a new engineer understand the system within their first 30 days?

- Are naming conventions, folder structures, and data flows consistent?

- Is the “happy path” documented and easy to follow?

- Are assumptions explicit rather than tribal knowledge?

Ownership & Boundaries

- Is ownership clearly defined at each layer (ingestion, transformation, consumption)?

- Do teams know who to contact when data looks wrong?

- Are responsibilities clear during incidents or failures?

- Are handoffs between teams documented and understood?

Observability & Trust

- Can the team easily tell if data is fresh?

- Are partial or silent failures surfaced quickly?

- Are there checks for schema changes, volume anomalies, or missing data?

- Can issues be debugged without deep system archaeology?

Designed for Change

- Can schemas evolve without breaking downstream consumers?

- Is raw data isolated from business logic?

- Can new sources be added incrementally?

- Is it possible to refactor or unwind decisions without a full rewrite?

Human Cost & Sustainability

- How much undocumented knowledge is required to operate the system?

- Can someone make changes safely without fear of cascading failures?

- Is the system understandable under pressure?

- Does the stack reduce cognitive load rather than increase it?

Rethinking What “Good” Means

A good data stack isn’t the most feature-rich or impressive.

It’s the one that:

- Behaves predictably under change

- Scales with both data and people

- Enables correct decisions, consistently

Tools will change. Teams will change. Requirements will change.

Stacks that are built on clear principles tend to outlast all three.

→ Download the full evaluation checklist: Resources