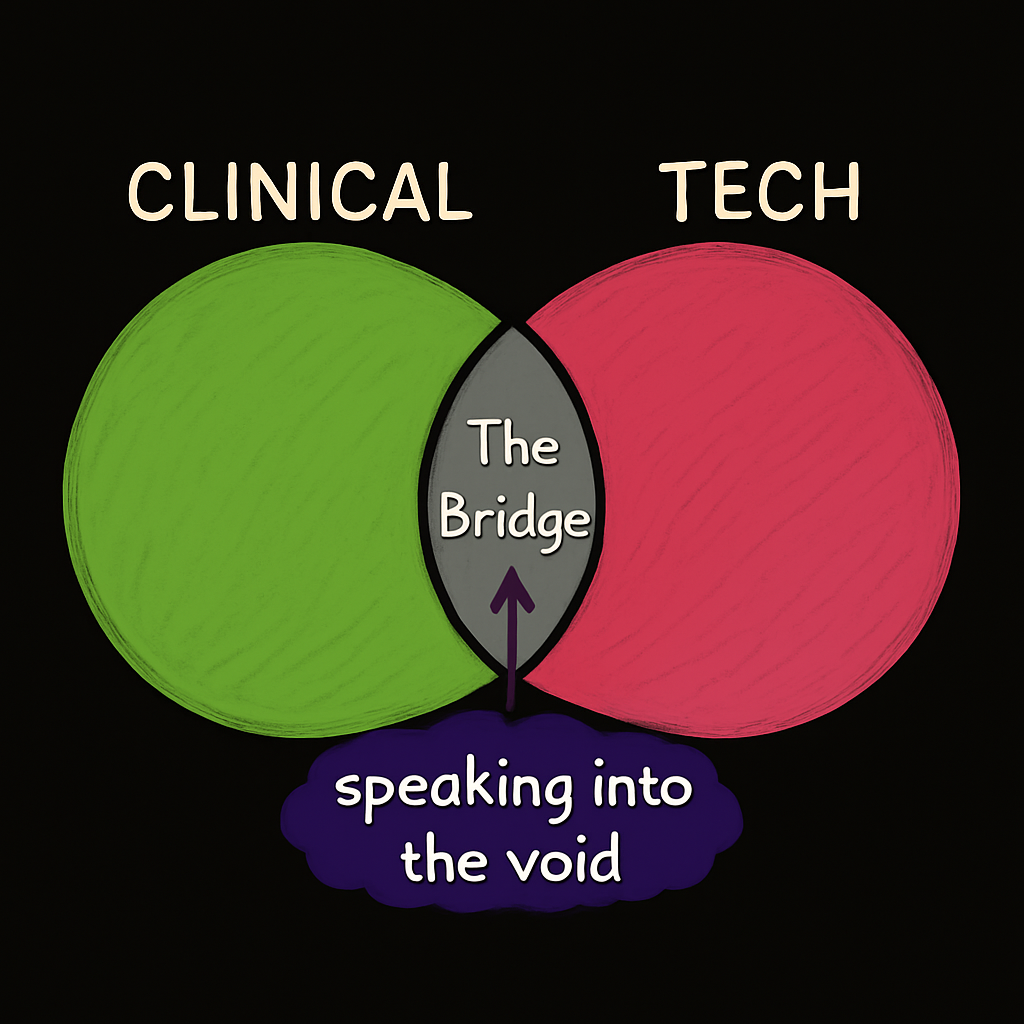

Too Tech for Clinical, Too Clinical for Tech

Image created by the author

I work at the intersection of clinical research and modern engineering. One side is governed by regulation and caution, and the other by cloud platforms, automation, and an expectation of rapid iteration.

Somehow, I’m too tech for clinical and too clinical for tech. And it’s… a little like being bilingual in two dialects that don’t think they need translators.

The Clinical Side: “We Could Innovate… But Why Rush?”

The clinical research world isn’t opposed to innovation; it’s just heavily optimized for stability and compliance. Change is slow because:

- Every new system must be validated.

- Every process must meet regulatory expectations.

- The stakes aren’t just uptime and user retention; they’re patient safety and data integrity.

These are valid reasons, but they also mean that a lot of innovation falls into the “maybe someday” pile. If your system still works and still passes audits, the incentive to replace it is very low.

The Tech Side: “We Can Totally Rebuild This By Friday”

Modern engineers can design platforms in days that would take years to approve in clinical research. They see slow-moving processes and think, “This just needs better tooling.”

Except… it’s not just tooling. It’s also regulation, legacy interoperability, domain-specific standards, and workflows designed to satisfy auditors and sponsors — not just end users.

When a tech team looks at clinical systems, they often underestimate:

- The constraints that are non-negotiable.

- The rules that can’t be “optimized away.”

- The hidden complexity that’s invisible until you try to change it.

Why the Gray Area Matters

Working in this gray area means understanding two very different sets of priorities and being able to explain them to each other without either side glazing over.

It’s about:

- Translating “this is how it’s always been done” into “here’s how it could work better — without breaking the rules.”

- Showing fast-moving engineers that not all obstacles are “technical debt” — some are guardrails that exist for a reason.

- Finding solutions that feel like progress to both sides, even if they define progress differently.

The bridge doesn’t just connect two sides — it’s what keeps progress alive. ∞

The bridge is the only thing that keeps them moving forward.

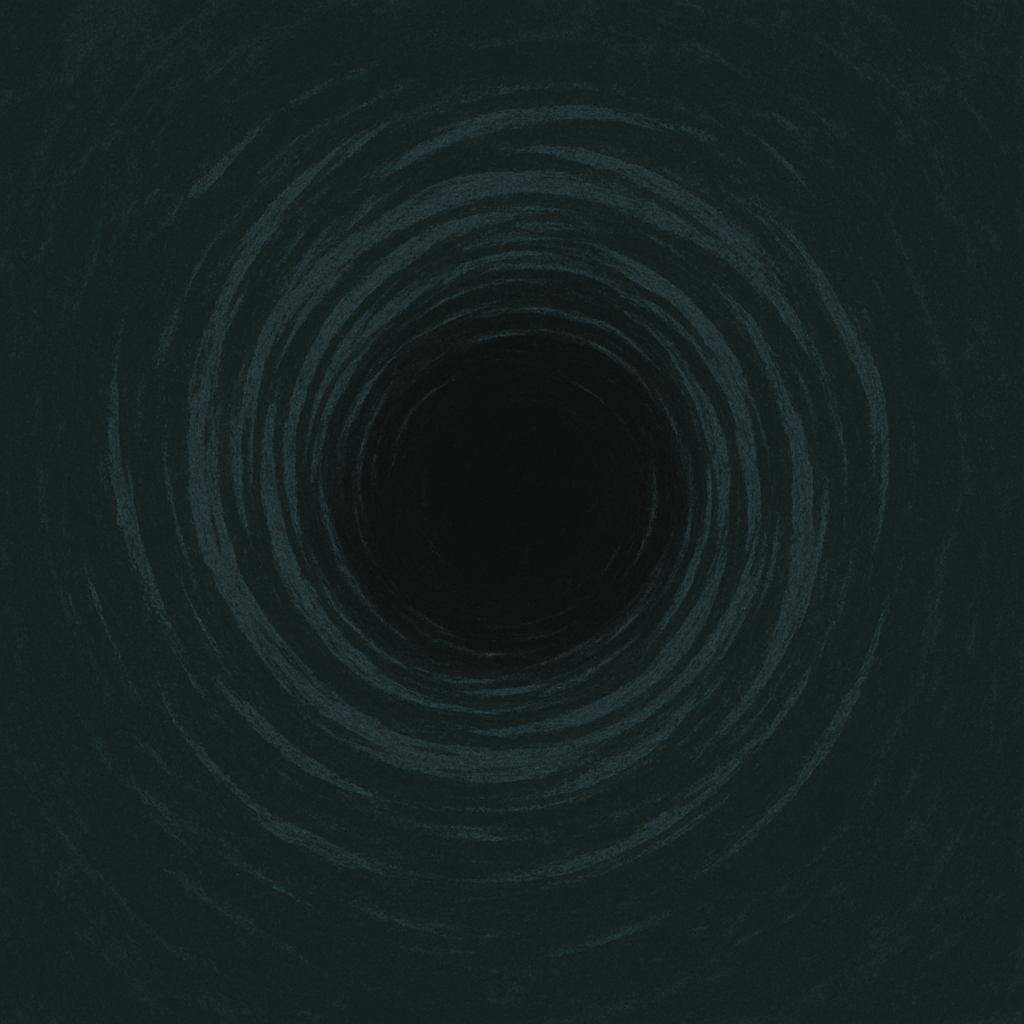

The Part No One Talks About

Image created by the author

Here’s the point: being in the middle feels like speaking into the void.

The clinical side has the power to change but not the will — their incentives are tied to compliance, not transformation. The engineering side has the skills to change things but not the desire, since the complexity is too messy, the regulations too restrictive, and the work is too far removed from what they know.

That leaves a very small group of people — people like me — who both understand the potential and care enough to try.

It’s a strange kind of isolation. You can see the path forward, but most of the audience you’re trying to reach is either uninterested, overwhelmed, or incentivized to keep things exactly as they are.

If you don’t try to bridge the gap, nothing changes at all.

Why We Keep Choosing Pain Over Progress

Here’s the truth: many of the problems we face in clinical research already have elegant, battle-tested solutions in the wider tech world. Data ingestion, workflow automation, secure audit trails — these are not unsolved problems. Modern engineering has been tackling them for years, if not decades, often with open-source or cloud-native tools that are more secure, scalable, and maintainable than what we’re using now.

So why don’t we use them?

Partly because the vendor ecosystem around pharma and regulated healthcare is built for one primary goal: meeting regulatory requirements. That’s important — critical, even — but it’s not the same as building with modern engineering or security best practices in mind. The result is software that passes audits but feels like it was designed in another decade… because it was.

These systems are often painful to use: clunky interfaces, rigid workflows, limited integration capabilities, and an overall sense that the user experience was an afterthought. And yet, they stay entrenched because:

- They already “work” for compliance.

- Switching is seen as high risk.

- The culture rewards stability over experimentation.

We pay huge sums for “customizable” tools only to find that customization is priced so high it’s essentially off-limits.

And then there’s vendor lock-in — the quiet trap that keeps the cycle going. I’ve seen systems that violate the most basic IT principles — like one software vendor’s database system that defaulted every new user role to the highest privilege level and gave us no way to change it. That’s security 101: least privilege. The “solution?” Require every user to manually downgrade their own access every single time they logged in.

This is a disaster waiting to happen from a security and data integrity perspective. It guarantees privilege creep, makes audit trails meaningless, and turns basic access control into a gamble on whether someone remembers an extra step.

Does that sound like a solution to you?

So instead of getting the flexible, industry-specific tool we paid for, we’re left paying extra for workarounds just to make it usable at all.

Are we paying for a solution, or for the privilege of staying stuck?

The irony is that the safest path forward may not be to reinvent from scratch, but to adapt proven, modern systems — the ones already used successfully in other industries — and apply them with the same rigor we use to validate any new clinical technology.

Until we do that, we’re choosing the comfort of the familiar over the possibility of the better.

That choice has a cost, even if it’s not measured in revenue or patient safety — it’s measured in the day-to-day frustration of the people trying to actually get the work done.

The Real Challenge… And Opportunity

This gray area can be frustrating, but it’s also where the most meaningful change happens. Progress here isn’t about grand overhauls — it’s about finding small, strategic incramental shifts that work for teams.

It’s where you can:

- Spot opportunities to simplify without oversimplifying.

- Introduce improvements in a way that feels safe to adopt.

- Build trust so that when bigger changes are needed, both sides are ready for them.

It’s not about moving fast — it’s about moving smart, earning buy-in, and fixing the right things in a secure and compliant manner.

If you’re in this space too, you know the tension — and the silence, but you also know that the people who can bridge these worlds are rare, and necessary.

We may be few, but we’re the ones who show what’s possible.

That’s what being too tech for clinical and too clinical for tech is all about.

💬 If you’re enjoying the ideas here and want to stay connected, feel free to connect with me on LinkedIn. I’d love to stay in touch with others thinking about the future of clinical data and systems design.

Disclaimer: This article reflects my personal views only and is for informational purposes. It does not represent professional advice or the positions of any past or current employer. No confidential or proprietary information is shared, and I disclaim all liability for how you use its content. Third-party links or tool mentions are not endorsements.